South Tombs Cemetery 2007

Wendy Dolling

Contents

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

1.2 Excavation aims

1.3 Site description

2 Excavation results 2007

2.1 Excavation area

2.2 Methodology

2.3 The archaeological findings

2.3.1 Post-Cemetery Period: accumulated fill

2.3.2 Grid Square G 52

2.3.3 Grid Square H52

2.3.4 Grid Square I52

2.3.5 Grid Square J52

2.3.6 Grid Square K52

2.3.7 Grid Square L52

2.3.8 Grid Square M52

2.3.9 Surface Collection

3 Discussion of findings

3.1 Burial method, density and spatial distribution

3.2 Burial disturbance

3.3 Potential reburials

3.4 Artefacts

Publications cited

Report on the human remains by Melissa Zabecki

Appendix 1. List of Units according to Grid Square (downloadable pdf file)

Acknowledgements

The 2007 season of excavation at the South Tombs Cemetery was carried out as part of the Egypt Exploration Society’s 2007 season of fieldwork at Tell el-Amarna, under the general direction of Barry Kemp. Part of the expenses were defrayed by grants from the Institute of Bioarchaeology and from the King Fahd Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies (University of Arkansas) arranged through Prof. Jerry Rose. The personnel of the excavation and associated research were as follows:

Archaeological Site Supervisor

Wendy Dolling

Archaeological Field Assistants

Anna Stevens

Rick Colman

Excavation Team

Hosni Osman Mehanni

Yahya Sadek

Bakr Amin

Abuzeid Azedin Abuzeid

Abdel-Hafiz Abdel-Aziz

Osman Ahmed Osman

Saleh Osman

Ahmed Mokhtar Mahmud

Bakr Nasr ed-Din

Mostafa Rabia Fathi

Mahdi Ahmed Abdel-Nazir

Hillal Mohammed Omar

Mohammed Abdel-Alim Hussein

Gamal Abdel-Halim Hassan

Mohammed Abdel-Malik Nassar

Abdel-Malik Mohammed Abdullah

Abdel-Aziz Abu Aleaqa

SCA Inspector

Mr Gamal Abu Bakr

Physical Anthropology

Prof. Jerome Rose

Melissa Zabecki

Objects Registrar

Dr Anna Stevens

Pottery Analysis

Dr Pamela Rose

Archaeobotany

Dr Alan Clapham

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Excavation of the Amarna South Sombs cemetery commenced in 2006 following the discovery of surface skeletal remains during 2003 and 2005 surveys of the area (Kemp 2003, 2005, 2006). In 2006 a 5m x 35m area was excavated on the eastern slope of a large wadi and a series of disturbed burials were identified (Ambridge and Shepperson 2006). In 2007 the investigation continued with excavation of a strip of grid squares running parallel to the northern edge of the 2006 area (Figure 1). The 2007 excavation season ran from the 3rd of March to the 15th of April.

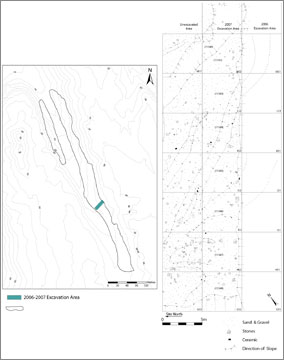

Figure 1. Topographical plan of the South Tombs Cemetery (prepared by H.Fenwick) & detailed surface plan of 2007 excavation area (prepared by W.Dolling)

1.2 Excavation aims

Prior to commencement of investigations at the South Tombs Cemetery archaeological evidence for New Kingdom burial practices at Amarna was restricted to that of the elite or noble residents. The methods of internment, burial material and any cult or ritual practice associated with the burials of the general populace of Akhetaten were unknown. The site is therefore of particular significance within the archaeological record of Amarna due to its potential to illustrate the burial practices of this previously unrepresented group. With this as a background the main aim of the 2007 excavation season was to gather archaeological evidence that would enable a determination of the burial practices evident at the site. Questions such as body orientation, utilization of grave goods and burial containment were main areas of interest. Patterns of cemetery disturbance exhibited at the site and the temporal relationship of disturbance and cemetery utilization was a sub-theme identified as a result of the 2006 excavation. An understanding of the physical layout of the cemetery and how it may have functioned as a place set within the broader landscape and social activity of the city is a longer-term objective that may be achievable through ongoing excavation. In addition a major aim of the South Tombs Cemetery project is to recover skeletal material for osteological analysis in order to answer questions such as population demographics and palaeopathology of the residents of Akhetaten (Rose 2006a and b).

1.3 Site description

The site is located on the eastern slope of a large wadi the mouth of which opens onto the Amarna plain. The east bank of the wadi initially drops relatively sharply downwards from the plateau but at a distance of approximately 40–60m from the current wadi floor the degree of slope flattens out and a relatively gentle slope continues downwards. Approximately 2m from the floor of the wadi proper the surface again drops sharply to base level. As such the embankment provides a large open area, which would have served as a suitable space for a cemetery of significant size. Though it is not possible to accurately determine to what degree the current topography varies from that of the Amarna period, excavation so far seems to point to a series of depositional and erosion phases at the site. It is therefore probable that the current limit of the eastern embankment varies only slightly from that of the Amarna period. Based on the survey findings and the topography of the landscape it is likely that the cemetery extends over much of this eastern end of the wadi and also includes a smaller area on the western embankment (Figure 1).

2 Excavation results 2007

2.2 Excavation area

During the 2007 season an area of 175 square meters was excavated consisting of a series of contiguous 5m x 5m grid squares (G52–M52). These grid squares extended in an approximate east-west strip running adjacent to the northern edge of the area excavated in 2006. As a result the excavation grid is aligned to a site north established during the 2006 season rather then true magnetic north.

General discussion of orientation in this report relates to site north; the exception is the orientation of burials which are described in relation to magnetic north. At commencement of excavation a contiguous surface deposit covered the entire investigation area consisting of loosely compacted sand with a minor to moderate gravel content. There were a number of distinct channels of variable depth cutting through this surface, most likely formed due to a natural process of water runoff. There were scattered limestone boulders resting on or partially imbedded in the surface and a minor amount of ceramic. No indicators of burial location were visible at this surface level (Figure 1).

2.2 Methodology

The site was excavated manually and all spoil was sieved prior to being discarded. Each recognized deposit and/or feature was given a distinct unit number using a sequential numbering system that applies to the entire site of Amarna. The South Tombs Cemetery is designated as Grid 14 within the Amarna site-numbering system.

Bone groups were assigned an Individual No. at the time of excavation when at least 50% of a complete skeleton could be determined to be articulated or clearly associated. If a group of articulated and associated disarticulated bone was excavated from an original burial context, that is from within a discernable burial pit, then less then 50% of an individual may still be identified by an Individual No. The sequence of numbering continued from that utilized in 2006, identified individuals in 2007 commencing with No. 23. In addition, a register of skulls was maintained to aid in determining the minimum number of individuals represented at the site. Skull numbering in 2007 commenced at 40; at the time of commencing the 2007 excavations analysis of the 2006 skeletal material was incomplete so that the exact number of skulls represented in this assemblage was uncertain. Following consultation with Prof. Jerry Rose the number 40 was chosen to avoid any potential double numbering of skulls.

Clusters of bone that were disarticulated and could not be securely assigned to an individual/s at the time of excavation were given a distinct unit number but not assigned an Individual No. In post-excavation analysis additional individuals were able to be identified from these bone clusters. All discussion of post-excavation analysis within this report is based on information provided to the author by Melissa Zabecki.

In determining the degree of weathering of any skeletal material a visual inspection was undertaken at the time of excavation. Bone described elsewhere in this report as weathered is bone that appeared completely desiccated and bleached of colour from exposure to sun and/or wind. In addition some bone had deteriorated further to become extremely brittle with the bone loosing its structural integrity. Bones that had not undergone significant exposure retained a degree of moisture visible as a brownish colour to the bone and were less brittle. An independent description of bone deterioration was made post-excavation by the physical anthropology team. The term bone as used in this report generally relates to human skeletal material unless otherwise specified. It is possible that some fragments of bone that were identified as human at the time of excavation may on analysis prove to be from other mammalian species.

The analysis of botanical material from the 2007 excavation season is ongoing; unless otherwise specified the species and plant type for recovered material is as yet unknown.

2.3 The archaeological findings

In describing the excavation findings a description of the significant units encountered in individual grid squares is provided followed by a discussion of the excavation area as a whole. Appendix 1 presents a description of all units identified during the 2007 season in table form. All squares excavated in 2007 form part of a larger grid set out during the 2006 season and includes squares G52–M52, G52 being at the western or wadi end of the grid. In addition to the main excavation strip some surface collection of exposed bone in the immediate vicinity was undertaken.

Prior to commencement of excavation a surface plan was made of the entire strip of grid squares. A decision was made to plan the adjacent strip G53–M53 as the sandy surface of the site is quickly disturbed by foot traffic and it would be necessary to utilize this space to access the excavation area. The southern limit of the 2007 excavation area was the northern edge of the 2006 grid squares. There was a significant degree of baulk collapse along this line in a southerly direction so that a portion of unexcavated sand had fallen in to the 2006 excavation area. As it was not possible to determine what was accumulated sand and what was baulk collapse it remained unexcavated within the 2006 excavation area (See Figure 1).

2.3.1 Post-Cemetery Period: accumulated fill

During the initial phase of excavation a series of slightly variable sand deposits were removed across all grid squares. Variations included the degree of compaction and relative proportions of sand to gravel. Though these variations were significant enough to warrant identification as independent fill units the transition point between units was often blurred. There was a small amount of scattered bone recovered from these layers all of which was significantly weathered. These deposits have been identified as accumulated sand, post-dating both the interment of burials at the cemetery and any subsequent robbing activity. The deposition of sand is unlikely to have been a completely linear process as variations in wind direction must have, as they continue to do, both eroded and deposited fill at the site.

Below the level of this accumulated sand several phases of activity were identifiable. At least three types of disarticulated bone clusters were evident as well as a series of disturbed burials. Though many of the burials display similar characteristics there is a degree of variation in the depth of the overlying deposits, nature of the underlying fill and the associated material culture. In order to display both the similarities and variations a brief description of the burials and bone clusters from individual grid squares is presented followed by a discussion of the excavation area as a whole.

2.3.2 Grid Square G 52

In Grid Square G52 the removal of accumulated fill revealed two in situ burials at variable depths of excavation and several bone clusters.

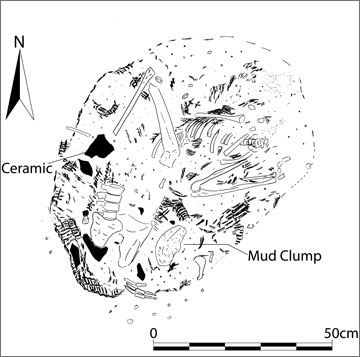

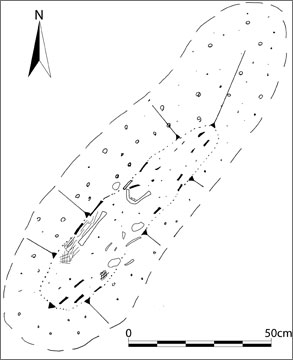

Burial Individual No. 24 – Unit (11574)

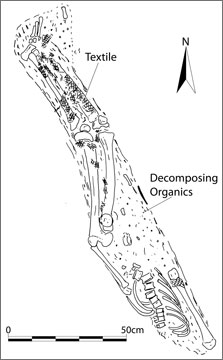

In the north-west quadrant of the square a relatively in situ burial (Individual No. 24) was exposed (Figure 2). The body was lying with legs slightly bent and rotated to the right and was orientated in a south-east/north-west direction with the head originally in the south. Most of the thoracic vertebrae and rib cage were articulated but the pelvis, sacrum, skull and the majority of the arm bones were absent. The body was completely skeletonized but the bones did not exhibit significant weathering. Both legs were partially covered by remnants of textile, which though fragmentary appeared to be strips of linen wrapped around the limbs. The body was covered by, and was resting upon, poorly preserved matting constructed of plant material. Though poorly preserved the distribution of this fragmentary matting suggests that it was originally wrapped around the entire body.

Figure 2. Individual No. 24

Bone Cluster – Unit (11577)

At an equivalent depth of excavation and positioned to the north-west of Individual No. 24 was a cluster of disarticulated juvenile bones – Unit (11577). There were some vertebral elements but the majority of the skeletal material consisted of disarticulated long bones, all bones being only slightly weathered. The close vicinity of the bones, comparable size, i.e. age group, and degree of weathering suggested they were most likely the bones of one individual. Post-excavation analysis indicated that the bones were in fact from one individual of indeterminate sex but aged from 5–10yrs. A few small fragments of plant stems were contained in the cluster but no artefacts.

Following the clearance of this bone cluster and the burial of Individual No. 24 a layer of underlying fill was excavated across the entire grid square exposing two additional bone clusters; in the central area Unit (11614) and in the south-east corner Unit (11594).

Bone Cluster – Unit (11594)

Unit (11594) was first revealed as a group of partially articulated foot bones – tarsals, metatarsals and phalanges – which ongoing clearance revealed as continuing into the 2006 excavation area, grid square G51. Excavation was extended into this square to expose the limits of the bone cluster. The lower legs, right and left tibia and fibula were lying in alignment with each other. The proximal end of the tibiae and fibulae were weathered to a white colour, the remainder of the bone length retained some moisture and was light brown in colour. It seems most likely that the southern ends of the bones have been partially exposed, possibly by baulk collapse following the 2006 excavation season. If so it raises an interesting question of rate of desiccation and has implications for interpretation of the robbing activity at the site.

On excavation, the leg bones were found to be partially covered in poorly preserved textile and to have stick or reed matting beneath them. It is possible that the position of the legs marks the original burial position and orientation of an individual, but the fact that the feet were disarticulated from the legs raises the possibility of the limbs being somewhat displaced from their original burial position. This cluster could as a result not be clearly designated as an in situ burial. Post-excavation analysis of the bones assigned them to a single person, a male aged between 18–22 yrs.

Bone Cluster – Unit (11614)

Bone cluster (11614) was located in the central area of the grid square. The bone was in a very poor state of preservation, being extremely brittle. Bones identified at the time of excavation include pelvic fragments and possible vertebrae. There were also a few small fragments of textile and some reed or plant fibre fragments within the cluster. These fragments of plant were of the type used to construct matting found in more intact burials. Ongoing clearance of surrounding sand revealed a partially articulated in situ burial (Individual No. 33).

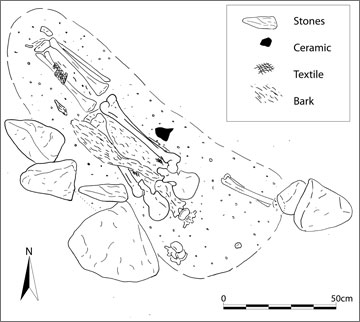

Burial Individual No.33 – Unit (11674)

Individual No. 33 was found lying in a poorly defined shallow pit cut into a sand and gravel surface – Unit 11681. Post-excavation analysis has identified the individual as a c. 20yr old male. The body was in the extended position lying supine and aligned approximately south-east/north-west, head to the south. A cluster of stones – Unit [11640] – were found resting on the wrapped feet and ankles of the burial (Figure 3). There were four large stones included in this cluster. Resting on top was a piece of white limestone, relatively flat on two sides and roughly hemispherical in shape; it was severely eroded with no definitive working marks. Underlying this white limestone boulder were three abutting stones of grey limestone all with only minor erosion and no definitive chisel or working marks. No bonding material was found between the stones but they did fit relatively snugly together and seem to have been purposefully placed. The stones are clearly associated with the burial and must have served to mark and/or protect the grave.![Figure 3. Grid Square G52. Stones cluster [11640] associated with Individual 33. Cluster (11643) in south-west corner. View site south](../../../../images/recent_projects/excavation/south_tombs_cemetery/2007/3.jpg)

Figure 3. Grid Square G52. Stones cluster [11640] associated with Individual 33. Cluster (11643) in south-west corner. View site south

The skeleton itself had been disturbed with the pelvic region, lower arms and head removed. The rib cage, thoracic spine, legs and feet remained in their articulated position. All bones were completely skeletonized but well preserved. The legs were positioned in alignment with each other with the feet turned slightly to the west, the left foot resting partially on top of the right. The upper arms were aligned alongside the torso. In situ bones were covered by matting, which consisted of flattened plant material (possibly stems) woven together with twisted fibre rope. The matting though very friable could be clearly seen lying under, around and over the lower legs. It was less well preserved over the reminder of the body but fragmentary traces indicate that it was originally wrapped around the entire length of the individual. In addition, traces of textile were found directly overlying and partially adhered to the bones. Much of the textile was in a poor state of preservation but the best preserved fragments covered the rib cage and consisted of strips of woven cloth rather then a garment. The right humerus and both legs had traces of textile wrapped around the individual limbs.

Following the excavation of Individual No. 33 the limits of a shallow ovoid were apparent. At approximately the mid-point along the western edge of the pit there was a slight scoop that seems to be a deliberate cut into the side of the burial. This may be the result of robbery focusing on the pelvic region of the body, a pattern that was repeated in a number of the burials.

![Figure 4. Individual No. 33 following removal of stone cluster [11640]](../../../../images/recent_projects/excavation/south_tombs_cemetery/2007/4.jpg)

Figure 4. Individual No. 33 following removal of stone cluster [11640]

Bone Cluster – Unit (11643)

In order to clear the burial of Individual No. 33 additional sandy fill was removed across the grid square. During this process a cluster of bone was exposed in the south-west corner of the square. This group of disarticulated bone was surrounded by a large amount of poorly preserved fragmentary timber, possibly from a timber coffin. Some of the wood fragments had traces of grayish-pink gypsum plaster adhering to them. There were also small fragments of fibre rope, textile and plant stems contained within the deposit. Skeletal material recovered included at least two distinct individuals as both neonate bones and the tarsal bones of a large adult have been identified in post-excavation analysis. Only small percentages of the total skeletons were contained in the cluster. The cluster was resting on a compact sandy surface, Unit 11682, with significantly increased gravel content when compared to the sand surrounding the cluster. The transition point between the two deposits is clear. This gravel-rich surface was only exposed in a small area due to time constraints but examination suggests it may be a natural surface.

2.3.3 Grid Square H52

In grid Square H52, following the removal of successive deposits of accumulated sand and gravel, a similar pattern of disarticulated bone clusters and partially disturbed in situ burials was found.

Burial Individual No.23 – Unit (11572)

The burial of Individual No. 23 comprised a partially articulated skeleton, the lower limbs and pelvic region including the lumbar vertebrae being preserved (Figure 5). The body was in the prone position – lying face down – and was orientated approximately south-east/north-west with feet at the northern end. There were a small number of scatted bones in the immediate vicinity including a radius, ulna and vertebral segments. With the exception of one small patch of tissue on a tibia the body was completely skeletonized. Textile fragments were found adhering to the lower legs; probably strips of linen. Lying over and partially under the right hip area was a sheet of bark identified as tamarisk. There was also plant material under the body but it was too poorly preserved to recover and identify.

Figure 5. Tibiae and fibulae of Individual No. 23 showing remnants of textile

No visible burial pit was discernable but the nature of the surrounding sand may have precluded the identification of any pitting in this relatively loosely compacted sand. There are several stones – un-worked limestone – forming a rough perimeter around the body (Figure 6). Though not a distinct structure their concentration around the body does support the idea that these stones were associated with the original grave. Apart from the prone positioning there is no other evidence that suggests the body was not in its original burial location. It has clearly been disturbed during a robbing period at the cemetery but there is every possibility that the body was originally interred in the prone position as has occurred in at least two other cases at the site. Post-excavation analysis has identified the individual as a 20–35yr old male. Underlying the burial and covering the remainder of the grid square was a slightly compacted deposit of sand and gravel. The removal of this layer exposed several bone clusters and additional in situ burials.

Figure 6. Individual No. 23 and surrounding stones

Bone cluster – Unit (11599)

This bone cluster was located in the southern portion of the grid square and consisted of a moderate amount of disarticulated bone and associated organic material including reed or stick matting fragments, fibre rope and human hair. Ongoing clearance of the deposit revealed that it directly overlaid an in situ burial (Individual No. 35).

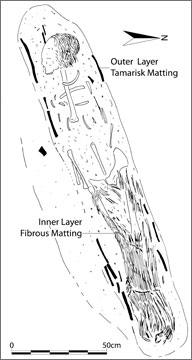

Burial Individual No. 35 – Unit (11671)

The excavation of bone cluster (11599) exposed an articulated torso, arms and head of a juvenile or small adult with associated textile and matting. The articulated portion of the burial was lying in the prone position, the head facing directly down (Figures 7 and 8). It was aligned approximately north-east/south-west with the head at the north end. All vertebral segments of the neck, torso and lumbar spine were articulated and in alignment. The ribs were also in alignment with both scapulas and arms articulated. The hands were partially disturbed but some of the phalanges and the position of the radius and ulna indicated that originally the hands had been placed in the pelvic area. Though the pelvis and legs were absent there was a slight depression and organic discoloration of the sand marking the original location of the lower half of the body. It is most likely that this burial was found in its original position; the lower limbs having been removed by robbers, though admittedly this is somewhat unusual. There is no indication that the body has been turned over; rather it seems to have been interred face-down.

Figure 7. Individual No. 35

The body was wrapped in openwork matting, probably tamarisk stems, which were tied together with fibre rope. There was also a thicker two-ply fibre rope wrapped around the matting as a whole. Beneath this outer matting was a second inner layer overlying the head and shoulder region of the body. This matting was made of flattened soft plant stems tied together with fibre rope. Beneath these mat layers were a few traces of textile.

Figure 8. Individual No. 35, showing prone position after removal of covering matting

The hair on the skull was well preserved, approximately shoulder length, black/brown with distinct soft curls, that did not appear deliberately styled and may be natural. As this individual was excavated at the end of the season only preliminary post-excavation analysis was possible. It has been identified as an adult but the age-range and sex are undetermined.

Bone Cluster – Unit (11616)

In the south-east corner of the grid square was another cluster of disarticulated bone. The bones included ribs, vertebrae, a mandible, scapula and fragmentary long bones. Most of the bones were significantly weathered. The cluster may extend further to the east into grid square I52; as time constraints prevented the excavation of that grid square to an equivalent depth this could not be established. Though the bones may belong to a single individual none of the bones were articulated. In post-excavation analysis at least a portion of the bones were found to belong to a 17–20yr old individual of indeterminate sex.

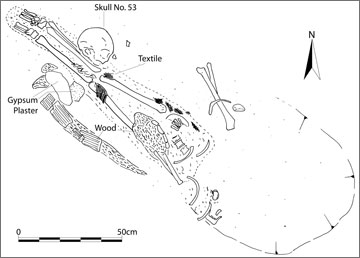

Burial Individual No. 29 – Unit (11645)

In the northern half of the grid square a group of disarticulated bone was found to be associated with a partially preserved burial (Individual No. 29). The articulated portion of the burial included the legs and pelvis of an adult. Post-excavation analysis has identified this individual as a 35–39yr old female.

Figure 9. Individual No. 29 and Skull No. 53

The body was resting in a poorly defined pit. It was difficult to accurately determine the exact limits of this pit as the fill was very similar to the surrounding sand into which the pit had been cut. There is every indication that even though the burial was disturbed the articulated bones were in their original burial location and alignment.

Bone Cluster/possible burial – Unit (11670)

Towards the end of the excavation period a weathered skull was revealed protruding out of a loose sandy deposit with associated smears of organic mater. The shape of this deposit was roughly ovoid and was of a size that suggests it may be a disturbed burial pit. Though unexcavated at present, if it proves to contain a burial it would form a line of five relatively evenly spaced burials within grid squares G52 and H52.

2.3.4 Grid Square I52

In Grid square I52 the depth of excavation was less then that achieved in adjacent squares. The absence of in situ burials revealed in this area is most likely representative of this decreased depth of excavation. Several layers of accumulated sand and gravel were excavated containing a small amount of scattered weathered bone. In addition there was a layer of more compacted sand that appeared to have been purposefully cut through possibly related to robbing activity at the cemetery. A bone cluster and a separate cluster of stone were identified by the removal of these sand deposits.

Bone Cluster – Unit (11646)

Unit (11646) comprised a cluster of disarticulated bone in the eastern half of the grid square that included long bones and vertebrae all of which were markedly weathered. There was a moderate amount of decomposing plant material in the vicinity of the bones, probably from matting associated with a burial/s. It became apparent that the cluster continued to a greater depth and may relate to a lower disturbed burial or a larger cluster of disturbed individuals. As time constraints prevented the complete excavation of the cluster a decision was made to collect only those bones that were exposed on the upper horizon of the deposit.

Stone Cluster – Unit [11685]

In the north-west quadrant of the square a cluster of stones surrounded by gravel-rich sand was revealed (Figure 10). There were three layers of stones in this cluster set in a small wall-like construction. No mortar or evidence of working was apparent on any of the stones. The base of the lower level of stones is imbedded into the gravel-rich sand. These stones were discovered towards the end of the season so that the structure was only partially excavated and its nature at this point is uncertain.![Figure 10. Cluster of Stones [11685]. View site west](../../../../images/recent_projects/excavation/south_tombs_cemetery/2007/10.jpg)

Figure 10. Cluster of Stones [11685]. View site west

2.3.5 Grid Square J52

Grid Square J52 was excavated to a slightly greater depth then the adjacent I52. A small amount of scattered bone including a disarticulated juvenile skull and small amounts of fragmentary matting were recovered from the upper accumulated sand deposits. Beneath these initial layers several clusters of disarticulated bone were found.

Bone Cluster – Unit (11585)

Unit (11585) consisted of a small cluster of bones all of which were significantly weathered. The bones included a mandible, pelvis and rib fragments. No other cultural material was found in association with this bone cluster. Post-excavation analysis has identified the mandible as belonging to a 25–35yr old individual, possibly male.

Bone Cluster – Unit (11587)

This large bone group was located in the north-east quadrant of the grid square. The bones were surrounded by slightly friable sand with a minor-to-moderate amount of gravel. There were bands of brownish discoloration within the surrounding sand, most likely decomposing organics such as reed matting or possibly textile. On excavation, these organic smears crumbled away and could not be more specifically identified. A large number of mainly disarticulated and weathered bones were contained in the cluster. The bones fall into two categories: small groups within the cluster that are clearly articulated and associated with each other; and bones that are disarticulated and cannot be clearly assigned to a particular bone group. The bones included a well preserved adult skull (No. 45) with an articulated mandible lying face down in the sand. Immediately to the east of this was a series of ribs lying in a group and most likely related to each other. There was also a radius and ulna independent of each other but each articulated to hand bones. Disarticulated bone included skull fragments, vertebrae, a mandible and long bone fragments. Analysis of the skeletal material is ongoing, but at least one 13yr old individual was included in the cluster of an indeterminate sex.

Figure 11. Bone Cluster (11587). View site south

Bone Cluster – Unit (11598)

Located to the south-east of unit (11587) was a second smaller cluster of disarticulated bone and organic material. Included in the cluster were several long-bone fragments as well as small fragments of botanicals, probably plant-stem matting.

Bone Cluster – Unit (11663)

This cluster of bones included three partial skulls, a femur, pelvic bones, a partial mandible and several ribs (Figure 12). None of the bones were articulated and all were surrounded by loose sandy fill.

Figure 12. Bone Cluster (11663). View site north

Original cemetery surface – Unit 11686 [note that 11686 needs to be underlined, 11686]

Once the thin deposit of sand and gravel upon which these bone clusters were resting was cleared an original cemetery-period surface 11686 was exposed. This surface was not excavated as it was revealed in the final days of the excavation season but consisted of a compacted gravel-rich surface into which a series of potential burial pits have been cut. There are seven such pits discernable as loose sandy deposits filling depressions in the surface. Future excavation should clarify the number of actual burials represented here, but at present the spread of the pits suggests a relatively random burial orientation and a much higher density than so far apparent in grid squares G52 and H52, with the majority of the available space in J52 having potentially being utilized for burials (Figure 30).

Potential infant burial – Unit (11673)

Towards the eastern edge of the square, and resting on this surface, was a slightly mounded area of gravel-rich sand with fragments of tamarisk matting on top (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Unit (11673). View site east

Given the size and shape of this mound it seems most likely that this feature – Unit (11673) – marks the original burial location of an infant. No skeletal material was evident at surface level and the mound itself remains unexcavated.

2.3.6 Grid Square K52

Stratigraphy in this square closely followed that exposed in J52 with loose fill overlying a series of bone clusters and a lower original surface. Fortunately, this original cemetery surface was exposed earlier in the excavation period so that sufficient time remained to investigate several of the revealed burial pits.

Bone Cluster – Unit (11569)

Unit (11569) comprised a small cluster of bones surrounded by sand and minor gravel. The recovered bone was all significantly weathered but identifiable bone types included a fragmented skull, ribs and long bones. There were also two small limestone boulders within the cluster of bone; neither appeared worked.

Bone Cluster – Unit (11622)

A cluster of disarticulated bones, several moderate size limestone boulders and a small amount of fragmentary ceramics was excavated in the southern half of the grid square (Figure 14). A small amount of botanical material, most likely reed or sticks from matting and fragmentary textile in a moderate amount, were contained in the cluster.

Figure 14. Bone cluster with associated ceramic fragments. The large stone to the left of the image marks the end of an underlying burial pit for Individuals No. 27a and b. View site south

The clearance of this cluster and surrounding sandy fill exposed a pit containing the disturbed burials of Individuals 27a and b. Immediately adjacent to the northern edge of the cluster was a second burial pit – Individual No. 34. This cluster is most likely material from one or both of these burials and forms a distinct mounded area. There were several large fragments of ceramic vessel/s within the cluster. It was not possible to determine if these vessels had been interred with the body or were originally placed at surface level

Original cemetery surface – Unit 11660 [keep this number underlined]

The two bone clusters discussed above were resting on and surrounded by contiguous layers of sandy fill covering much of the grid square. The excavation of these sand layers revealed a series of burial pits cut into a gravel-rich sandy deposit, an original cemetery period surface – Unit 11660. In the north-east corner of the square a gravel mound was exposed resting on top of this surface. Contained within this mound was a contracted burial.

Burial Individual No. 28 – Unit (11623) – contracted burial

This burial was initially identified as a cluster of bones when a disarticulated skull and femur became apparent protruding from a gravel mound (Figure 32). On excavation of the surrounding loose sand, these bones were found to be resting on top of a disturbed but in situ burial. At present this burial is unique at the South Tombs Cemetery in that the body was in a contracted rather then an extended position. Post-excavation analysis has identified the individual as a 35–50yr old person, possibly male.

Figure 15. Individual No. 28

Individual No. 28 was interred in a roughly circular pit or hollow within the mound; the body and associated material contained in woven basketry. The skull, lower limbs and lumbar spine have been disturbed and were found lying over and around the articulated portion of the skeleton. However, the thoracic spine, pelvis, coccyx, ribs and left arm with some hand bones remained articulated in their original burial position. An articulated foot was found resting under the buttocks area suggesting that the legs had originally been tucked up over the abdomen. The spine and pelvis were curled into a contracted position with the body lying on its left-hand side, head end to the north-east. The left arm was bent at the elbow with the shoulder extended slightly so that the partially articulated hand was resting in the vicinity of the head. The right arm was disturbed and lying disarticulated along the rear of the rib cage.

Within the partially preserved basketry surrounding the body was a moderate amount of fragmentary ceramic, several lumps of mud of an indeterminate nature and a small amount of scattered charcoal. Ceramic included the base of a New Kingdom amphora that has a blackened interior and may have originally been used as a lamp (Object no. 37986).

Several fragments of mammal bone were also recovered from within the burial space. Formal analysis of the bone is yet to be undertaken, but they have been tentatively identified as bone fragments from a young ovi-caprid, one fragment with distinct butchery cuts, and another fragment from a larger mammal possibly bovine.

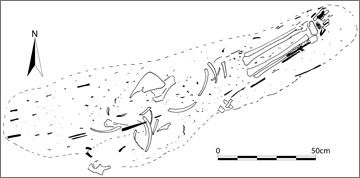

Burial Individual No. 27A and B – Unit (11665)

The clearance of the bone cluster (11622) discussed above and a thin layer of underlying sand exposed a distinct burial pit – Unit <11653>. This pit was significantly deeper than other burial pits so far excavated at the site, and was orientated approximately north-east/south-west (Figure 16). At the eastern end of the pit was a large rectangular limestone boulder embedded into a mound of gravel and several smaller stones (11664). None of these stones had signs of definitive working but, in particular, the larger upright stone was significantly weathered which may have destroyed any original working marks. The burial itself was markedly disturbed with most of the skeletal material having been removed from the pit. There was a large amount of fragmentary plant stems and scattered fibre rope, suggesting that the burial was originally wrapped in matting, as well as fragments of textile.

The only articulated bones were found resting on remnants of matting at the western end of the pit. Interestingly the articulated feet and legs of one individual (Individual No. 27a) were found as well as the articulated feet of a second individual (Individual No. 27b). The more intact individual seems to have been lying on its right side. The feet of the second individual are only partially articulated. Given the extensive disturbance of these two individuals it is possible that the excavated position does not reflect the exact original burial position. As the entire length of the right leg of Individual No. 27a is preserved it is likely that the general orientation, with feet at the southern end of the pit, is original. Analysis of the skeletal material has identified two adults, one a 35–50 yr old of indeterminate sex (Individual No. 27a) and the other a 25–35yr old female (Individual No. 27b). The distinct stone maker sets this burial apart from other burials in the vicinity, though this could be due to inconsistent preservation across the site.

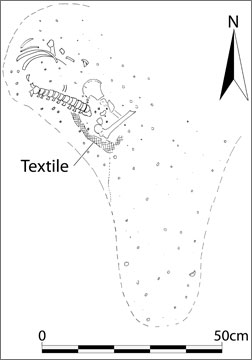

Burial Individual No.34 – Unit (11654)

To the south-west of the above burial was another oblong pit. This relatively shallow grave cut contained the disturbed burial of an individual identified in post-excavation analysis as a 40–45yr old female. The grave was orientated approximately east-west, with the head at the western end. The head and the majority of the torso had been disturbed though most of these bones were lying within or above the grave cut in a disarticulated state.

Figure 17. Individual No. 34

Unexcavated burials

In the south-west corner of the grid square clearance of the upper level of loose fill from an apparent pit revealed that it extended beyond the edge of the excavation area into grid square K51 – Unit <11650> (Figure 18). A small amount of disarticulated bone was recovered along with some fragments of fibre rope from this pit. This pit has a high probability of containing a disturbed burial but is as yet only partially excavated. An additional four possible burial pits were discernable as deposits of loose sand filling depressions in the cemetery surface – Unit 11660. Time constraints prevented the clearance of these pits (Figure 32).

Figure 18. Grid Square K52 showing spread of burial pits. View site south

2.3.7 Grid Square L52

Archaeological deposits in Grid Square L52 were in general comparable to those revealed in K52. Deposits consisted of a series of loose-to-slightly-compacted sand and gravel with some scattered bone, a lower level of disturbed bone clusters and, at base level, a series of disturbed but in situ burials cut into a sand and gravel surface. This surface 11687 was contiguous with the original cemetery surface exposed in the adjacent square K52 – Unit 11660

Bone Cluster – Unit (11582)

Unit (11582) was a small cluster of weathered bone, including a partial skull, surrounded by a fill of gravely sand.

Figure 19. Individual No. 25

Burial Individual No. 36 – Unit (11668)

The burial of Individual No.36 was initially identified as a cluster of disarticulated weathered bone. Ongoing excavation demonstrated that these bones were lying over and slightly to the side of a partially intact burial (Figure 20). The articulated bones were interred within a shallow ovoid pit orientated approximately west-east, feet at the eastern end. The majority of the body had been disturbed with only the lower legs and feet of the individual remaining in situ. The legs were in the prone position, feet extended, and had fragments of textile overlying them. Though the burial was markedly disturbed, there were remnants of plant stems and fibre rope comparable to more intact examples of tamarisk-stem matting associated with other burials. There was also a moderate-to-large amount of grey-brown fine-grained matter within the sand filling the burial pit and surrounding the in situ bones. This material is possibly ash, though the bones and surrounding linen did not appear to have been burnt so that it may be decomposing organics.

Figure 20. Individual No. 36

Burial Individual No. 37 – Unit (11669)

In the north-east area of the square a disturbed infant burial was located (Figure 21). The skeleton was poorly preserved and only one scapula and humerus remained articulated; most of the bone was markedly weathered. The burial seems to have been wrapped in textile and then in a plant-stem mat, and was orientated south-west/north-west with the head originally at the south end. Skeletal material was resting on a small mound of gravel that overlies the original cemetery surface in contrast to the adult pit graves. Post-excavation analysis indicated an age range of 2–3yrs; the sex could not be determined.

Figure 21. Individual No. 37

Burial Individual No.39 – Unit (11675)

This burial extended across Grid Squares K52 and L52, and consisted of an adult individual with scattered disarticulated bone resting on top of a partial articulated skeleton (Figure 22). There was a clearly definable though shallow burial pit associated with this individual. Articulated elements of the burial included the legs, feet, thoracic vertebrae, some ribs and both upper arms.

The burial was orientated approximately north-south with the feet at the southern end and was lying in the supine position. Fragments of textile were found around the articulated bone; the exact nature of the cloth is uncertain. An openwork matting of plant stems and fibre rope was found lying around and partially over the remnants of in situ bone. Following the removal of the skeletal material and surrounding fill a relatively well preserved portion of this tamarisk matting was found lying within the base of the burial pit (Figure 23). This matting partially adhered to the base of the pit. Without on-site conservation the chances of lifting this matting intact were felt to be low. It was therefore left in the base of the pit. Post-excavation analysis has identified Individual No. 39 as a male aged 35–50yrs.

Figure 22. Individual No. 39

Figure 23. Tamarisk matting revealed within the burial pit of Individual No. 39

Bone Cluster – Unit (11617)

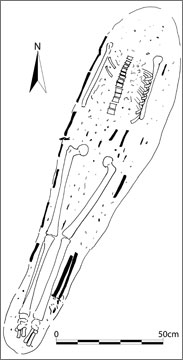

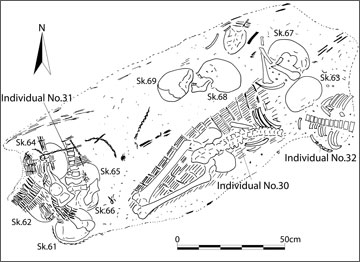

The excavation of a mound of gravel-rich sand in the south-east quadrant of this grid square exposed a large cluster of disarticulated bone and partially articulated skeletons (Figure 24). This bone group varies from other clusters within the 2007 excavation area in both the nature of the skeletal material and in the associated archaeological finds

Figure 24. Bone Cluster (11617) following removal of covering fill

There were a total of nine skulls contained in the cluster and at least three partially articulated individuals (Figure 25). One particularly well preserved torso and upper legs of an 8–10 yr old (Individual No. 30) was resting on a sheet of tightly woven matting. Two other less intact skeletons have been identified as a 10–12 yr old (Individual No. 31) and a 5–10 yr old (Individual No.32). In contrast, the skulls, with the exception of one 5-yr old, are all from adults. The cluster was also distinct in that the bones appeared to have been wrapped in basketry. This was particular apparent at the western end of the cluster where basketry could be clearly seen to lie under and over the bones with twisted fibre rope holding it in place. Though less poorly preserved at the eastern end of the cluster there was a distinct brownish smear of decomposing organic matter with fragments of identifiable matting, basketry and fibre rope delineating the limits of the actual bone cluster and covering the majority of the skeletal material. The cluster was also found to be resting in a slight hollow.

At present the exact nature of the cluster remains uncertain but it was clearly a deliberate collection of disturbed burial material and may represent an attempted reburial. The variable nature of bone clusters at the site is discussed in greater detail below.

Figure 25. Bone Cluster (11617) and burials in the vicinity. View site north

Potential unexcavated burial (11694)

At completion of the excavation season an unexcavated pit was visible cut into the surface of Unit 11687. The shape and size of this deposit suggests that it is an original burial cut.

2.3.8 Grid Square M52

The easternmost grid square varied somewhat from other excavated areas. At the commencement of excavation the removal of a thin lens of less then 5cm of sand from the north-east corner exposed a natural outcrop of limestone. This outcrop was found to continue in a downward slope towards the east and south covering a significant portion of the grid square. In the reminder of the grid square deposits of loose-to-slightly friable sand containing a small amount of weathered bone were cleared. Unlike the adjacent squares, no distinct bone clusters were encountered though there was one relatively well preserved disarticulated skull. One in situ disturbed burial was excavated, and at the completion of the excavation season several potential burial pits were identified.

Burial Individual No.26 – Unit (11634)

At the northern edge of the grid square was a disturbed in situ burial (Figure 26). The body was lying within a shallow pit cut into a gravel-rich deposit of sand, resting directly on top of the limestone outcrop. The burial extended beyond the square’s limits so that it was necessary to open a small sondage into grid square M53 in order to expose the entire burial.

Figure 26. Individual No. 26

This burial was poorly preserved. Much of the skeletal material had been removed and the upper surface of many of the bones had been either eroded or potentially sheared off during the robbing process. The body was orientated west-east, head at the west end. Most of the torso, the upper arms, a portion of the lower legs and feet remained in situ; the skull, pelvis, forearms and femora had been removed. The body was interred in a supine extended position and was resting on openwork matting constructed of tamarisk-plant stems. Fragments of this matting wrapped around the sides of the skeleton, and most likely originally covered the entire body.

Indeterminate Pit – Unit <11648>

To the south of the limestone outcrop a small ovoid pit was revealed. This pit was cleared of loose sandy fill and found to contain a small amount of fragmentary bone and plant stems. Given its size and shape the pit may mark the location of an infant or juvenile burial. However, unlike other pits containing disturbed burial material there was no sign of decomposing organic matter discoloring the base of the pit. It may, in fact, be an intrusive cut made by thieves

Unexcavated potential burials

The base level of archaeological deposits in this square was not reached during the excavation period. At the completion of the season a semi-compacted sandy surface, Unit 11690, was exposed. Several depressions were evident in this surface; there is a high probability that at least two of them are original burial pits. The exposed surface is at a higher level then the definite cemetery surface exposed in Grid Square L52, so that it is possible that ongoing excavation will reveal as yet unidentified burials at this eastern end of the site.

2.3.9 Surface Collection

At the commencement of the excavation season there was evidence that between the 2006 and 2007 season the site had been disturbed, presumably by an attempted looting of the site. The small mud-brick tomb exposed during 2006 and then reburied had been uncovered and some of the bricks removed and discarded on the surface, with digging activity surrounding it, exposing scattered weathered bone. To the north of the excavation area, in Grid squares K54 and L54, an irregular pit had been dug to a depth of approximately 1m; around the edges of this pit was additional scattered bone. Given the increased rate of deterioration of bone exposed on the surface a decision was made to collect these bone scatters.

Individual No.38 – Unit (11679)

In addition to surface bone collected at the commencement of the excavation period, baulk collapse along the northern edge of grid square G52 exposed a cluster of bones within grid square G53 (Figure 27).

Figure 27. Articulated lower legs and feet of Individual No. 38, overlying additional bone and decomposing organics

A small amount of surface sand, c. 5cm in depth, was cleared in the vicinity of these protruding bones to reveal the articulated lower legs and feet of an individual. Lying beneath the feet was a partially articulated torso and fragmentary disarticulated bone. All bone within this group appeared to be from one individual and so was designated as Individual No. 38. Underlying the lower level of bones was decomposing organic material, possibly matting though the preservation was too poor to determine accurately the type of matting represented. The jumbled nature of these bones precludes them from being identified as an in situ burial.

3 Discussion of findings

3.1 Burial method, density and spatial distribution

The South Tombs Cemetery has provided a body of material evidence reflecting burial practices of the general populace of Akhetaten. Despite the extensive disturbance at the site, sufficient skeletal and associated material culture is preserved to enable the orientation and nature of many of the individual burials to be determined.

During the 2007 excavation 18 individuals were identified and a total of 33 skulls were recovered. Post-excavation analysis of the skeletal material is ongoing, but 11 additional individuals have been identified by this process. The physical anthropology team has proposed that this represents a minimum number of 29 individuals. In addition to these excavated individuals there are indications that a significant number of unexcavated burials remain within the gridded area. For example, in Grid square K52 there are a probable total of nine burial pits of which only four have been excavated. In the adjacent square J52 there are potentially seven as yet unexcavated burials. Some of the disarticulated bone excavated in 2007 may be from disturbed burials located in these pits.

It has also become apparent that the base of the archaeological deposits had not been reached in the 2006 excavation area (Grid squares H51–K51). Definite cemetery surfaces and a number of burials exposed during the 2007 excavation are clearly at a greater depth then the base-level of the 2006 excavations. As a result, though an accurate density of burials can as yet not be determined, it is likely to be higher than the 56 individuals identified over the two excavation seasons. Given the potential size of the cemetery as identified by the 2003 and 2005 surveys, only 1–2% of the total area has been excavated. Though the project is in its infancy and any estimates of total burials must be considered tentative, a conservative estimate for the site may easily exceed 2000.

As is to be expected for a cemetery of this period the bodies were buried in the extended position; the one exception is discussed below. Significant variation in burial orientation continues to be evidenced at the site (Kemp 2007). There is no evidence that any of the bodies have undergone a process of mummification, being completely skeletonized. Three of the individuals were found lying in the prone position – face down – with every indication that this was their original burial position. It is probable that this positioning of the body is incidental in that, once the deceased was wrapped in matting, it may not have been immediately apparent which side of the bundle was the front of the body. This was demonstrated during the excavation of Individual No. 35, as it was not until both layers of matting were removed from the body that its prone burial position became apparent.

The majority of the skeletons had traces of textile associated with them. The exact nature of this textile was not always evident though at least some bodies were wrapped in linen strips rather than garments. At least two types of body covering or containment were utilized. The commonest outer wrapping was a form of relatively openwork matting formed of probable tamarisk plant stems and tied together with twisted fibre rope. Some burials have a second inner layer of matting. The nature of this inner layer is more variable but all types were formed from plant matter, and included strips of bark, sheets of possible date-palm husk and flattened plant stems or possible reeds. Much of this material is awaiting botanical analysis so that the exact species is not yet identified. Infant burials reflected similar burial preparation to the adult burials, as they had textile and fragments of matting associated with them; though the infant burials are poorly preserved so that comparisons are tentative at present. At least one infant and a potential unexcavated second infant were buried within a mound of gravel resting on top of the original cemetery surface rather than in a pit.

Individual No. 29 demonstrates the second main form of body containment. Fragments of wood and decorative gypsum plaster, remnants of a decorated timber coffin, were found in association with these in situ skeletal remains (Figure 28). The skeleton itself did not differ markedly from the remaining individuals, in that it was completely skeletonized and only fragments of associated textile were preserved. Whether this variation in burial equipment marks a difference in wealth, social rank or a temporal alteration in funerary practice is uncertain. In addition, a bone cluster with disturbed skeletal material was excavated containing fragments of wood, evidence of additional individuals that may have been buried in timber coffins (Unit – 11643).

Figure 28. Plaster and timber coffin fragments overlying skull No. 53 and Individual No. 29

Individual no. 28 differs from the remaining burials primarily as the body was interred in a contracted position (Figure 29). There are other elements of this burial that distinguish it, including the presence of animal bone within the grave, a mounded gravel burial area, and the use of basketry rather then matting to enclose the body. By comparison with the remaining burials, there was a relatively large amount of ceramic recovered from within the grave. This ceramic was in a fragmentary state and may only represent a small number of total vessels. It is difficult to understand the significance of this burial position at the South Tombs Cemetery.

Figure 29. Individual No. 28

Though only a small proportion of the cemetery has been excavated, given standard New Kingdom burial practices it is unlikely to be a common type represented at the site. One possibility is that the individual is of a variant ethnicity to the remaining individuals, though there is nothing in the grave assemblage that marks the individual as non-Egyptian. Comparative analysis of contemporary contracted burials may help clarify the meaning of this burial method.

The spatial patterning at the cemetery is as yet difficult to determine given the small area examined. As has been pointed out by the physical anthropology team, there are a relatively small number of infants represented, which may be indicative of a separate location for infant burials. At Deir el Medina the 18th Dynasty eastern cemetery exhibited an apparent age-based distribution of burials, with infants, adolescent and mature adults being clustered in distinct areas (Meskell 1999, 2000). During the 2007 season, infants and a neonate were excavated, but the majority of the recovered individuals were juveniles and adults. Though the proportion of infants continues to be lower then expected, with regard to adults and juveniles there does not appear to be an age-based separation of burials. Likewise both male and females are represented at the cemetery without discernable separation in burial location. Figure 31 illustrates the distribution of burials according to age and sex from both the 2006 and 2007 seasons. Similarly there does not appear to have been a consistent variation in the type of material used to cover and contain the bodies based on age or sex. The small number of more elaborate graves with timber coffins is too few in number to draw any firm conclusions regarding burial distribution as it may relate to status.

3.2 Burial Disturbance

In terms of burial disturbance, both the 2006 and 2007 excavation seasons have established that in this portion of the cemetery the majority, and potentially all, of the burials have been disturbed. This disturbance seems to be due to a deliberate robbing process, in particular focusing on the head area with a secondary focus on the lower arm and pelvic region. As a result, the upper limbs and torso of many of the disturbed burials remain in situ while the head, forearms and pelvis are the most consistently disarticulated elements. Presumably this destruction occurred in the process of searching for jewellery or amulets attached to the neck area. Waist jewellery has been found at other New Kingdom sites such as Gurob, but it seems to have been less prevalent than neck, arm and hand adornment (Brunton and Engelbach 1927). As such, the pelvic region may have been disturbed incidentally in an attempt to locate valuables on the hands, which in many cases seem to have been resting in that region.

The exact historic point at which this robbing occurred is of interest but may be difficult to firmly establish. The 2006 excavation team has suggested that the robbing occurred in antiquity and there is nothing in the 2007 findings that would contradict this suggestion. In fact there is a one large cluster of bones – Unit (11617) – containing several partially articulated individuals and nine skulls that may represent an attempted group reburial of disturbed individuals. This interpretation is tentative and requires further investigation but if true would indicate that at least one phase of robbing occurred during the active use or maintenance of the cemetery. It is also interesting that in the exposed gravel surfaces with a high density of burial pits, there does not seem to be a significant degree of random pitting of the type that may be expected with unguided robbing activity. This gives support to the idea that, during the disturbance phase, the location of burials was discernable at surface level, possibly as gravely mounds or marked with limestone boulders.

In order to illustrate the stratigraphy evident over much of the excavation area the sequence of top plans from grid square K52 are combined in Figure 32. In reviewing this sequence there are indications that there may be more then one phase of disturbance at the site. The main phase of disturbance is exemplified by the disturbed burial material found within or in the immediate vicinity of the original burial pits (Figure 32.2H). This phase of disturbance is reflected in the stratigraphy over much of the excavated area. Following this disturbance, several deposits of sandy fill, relatively free of cultural material, accumulated over the disturbed burials (Figures 32.D–F); the most distinct of these deposits are units (11635) and (11576). Overlying this accumulated fill was at least one bone cluster – Unit (11599), a moderate amount of scattered bone and several distinct gravel lenses (See Figures 32.B–C). There are similar clusters and scatters of bone in other grid squares but, as in K52, they tend to represent a relative small amount of the disturbed burial material. It is possible that this second phase of disturbance is at least partially due to natural erosion forces, such as water run off, displacing archaeological deposits. It should also be noted that the depth of accumulated fill separating the two possible phases is in places less then 10 cm. It is possible that this does not represent a significant time lapse given the potential for rapid accumulation of sand at the site in periods of high wind.

3.3 Potential Reburials

In an attempt to understand the pattern of disturbance and burial at the site an examination of the characteristics exhibited by all bone clusters was undertaken. Three main types of clusters were identified.

Type 1

- Majority of the bone is disarticulated

- Not in the immediate vicinity of an in situ burial

- Minimal or absent additional material culture e.g. burial matting or basketry

- All bone in a relatively comparable state of weathering

Type 2

- Majority of the bone is disarticulated

- Position and osteology suggestive of association with an in situ burial i.e. directly overlying or within a burial pit and of compatible age and sex

- Fragmentary burial material such as linen, matting or plaster fragments may be associated with the bone cluster

- All bone in a relatively comparable state of weathering

Type 3

- At least a portion of the bones are articulated

- More then one individual is clearly contained in the cluster

- Basketry and or matting covering/enclosing the bone cluster

- Bones exhibit variable states of weathering or preservation

Cluster Types 1 and 2 can comfortably be explained as due to the activity of grave robbers. Both types of bone have been removed from buried individuals and discarded – Type 1 at some distance from the burial; however, given the density of burial exhibited in some areas of the site the distance from the original burial may in fact be minimal – Type 2 discarded in the immediate vicinity of the in situ skeleton. The prevalence of Cluster Type 2 implies that many of the bodies were disturbed and presumably searched for valuables within or relatively close to the grave itself.

Cluster Type 3 – Unit (11617) is less easily explained as being due to the activity of thieves. The multiple individuals represented clearly indicate a process of purposeful collection. To understand this as occurring in the setting of grave robbing it is necessary to look for a rationale such as a desire by the thieves to search the bodies in one location. There are a number of factors that point against this idea. As stated above, a significant proportion of the disturbed in situ burials are associated with Type 2 bone clusters (i.e. it was relatively common for the bodies to be searched within or adjacent to their graves). Inconsistencies in the state of preservation within the Type 3 bone cluster suggest that the skeletal material had variable periods of exposure or treatment prior to collection into the cluster. Possibly the most telling fact is that much of the bone remains contained within basketry or covered with matting. This would eliminate collective searching of the bodies as a rationale unless the thieves were interrupted before they had searched the bodies. Though poorly defined, the cluster – Unit (11617) – did appear to be resting in a shallow pit with gavel-rich sand mounded over it. At present the more likely scenario seems to be that this bone cluster type represents a deliberate collection and reburial of disturbed skeletal material.

In order to determine if Unit (11617) was an isolated case a large bone cluster excavated during the 2006 season was re-examined. The cluster in question was excavated from grid Square L51. From this cluster 11 skulls and the partially articulated skeletons of at least 6 individuals have been identified. Eight of the eleven skulls and three of the partially articulated skeletons were from adult individuals. At least a portion of the cluster was covered by basketry and or matting, and the bones show some variability in weathering; one skull had been completely blackened by burning prior to being placed in the basketry. Unlike Unit (11617) there does not appear to have been a discernable pit associated with the cluster. Whilst the evidence for reburial is by no means conclusive, if proven true it raises interesting questions concerning when, in the cemetery’s history, the reburials occurred and who carried out this process.

3.4 Artefacts

In terms of goods buried with or on the bodies of the individuals, no intact artefacts were found in any of the disturbed burials. Scattered fragmentary ceramics were recovered from the fill layers at the site and an occasional fragment was found in disturbed fill within the graves.

It is not possible at present to draw any firm conclusions as to the original positioning of these ceramic vessels and whether they represent grave goods interred with the deceased or were used at surface level in funerary or mortuary activities. The only other artefact type recovered from the site during this season was a small number of faience beads. These beads were recovered from loose fill, were isolated from each other and cannot be associated with any particular burial.

The minimal number of artefacts from the site suggests that the majority of individuals were buried with at most only a small number of items. Even with the degree of destruction evidenced at the site significant amounts of jewellery would most likely have left more trace in the archaeological record. The number of artefacts recovered is so minimal that the thieves were either extremely efficient or, more likely, there were in fact only a small number of artefacts at the site as a whole. Unfortunately none of the in situ burials excavated over the two seasons were undisturbed. Without intact examples no firm conclusions regarding the quantity and type of burial goods can as yet be drawn.

An index of the objects, prepared by Anna Stevens, is presented for download here as an excel spreadsheet (download spreadsheet here); it includes the objects collected during surface survey in 2005 and those found in 2006.

Figure 30. Location of excavated burials, surfaces revealed at the completion of excavation and the location of unexcavated burials

Figure 31. Spatial patterning of in situ burials excavated during 2006 and 2007, according to age and sex

Figure 32. Grid Square K52. Sequence of top plans following the removal of the surface deposit

Publications cited

Ambridge, L. and M. Shepperson, 2006. ‘South Tombs Cemetery’, in B. Kemp, ‘Tell el-Amarna, 2005–06.’ Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 92, 21–56.

Brunton, G. and R. Engelbach, 1927. Gurob. London, British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Quaritch.

Kemp, B., 2003. ‘Tell el-Amarna, 2003.’ Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 89, 10–11.

Kemp, B., 2005. ‘Tell el-Amarna, 2005.’ Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 91, 22–4.

Kemp, B., 2006. ‘Tell el-Amarna, 2005–06.’ Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 92, 21–56.

Kemp, B.J., 2007. ‘The orientation of burials at Tell el-Amarna.’ In Z. Hawass and J. Richards (ed.), The Archaeology and Art of Ancient Egypt: essays in honor of David B. O'Connor. Cairo, Supreme Council of Antiquities Press, 21–31.

Meskell, L., 1999. ‘Archaeologies of life and death.’ American Journal of Archaeology, 103, 181–99.

Meskell, L., 2000. ‘Cycles of life and death: narrative homology and archaeological realities.’ World Archaeology 31, no.3, 423–42.

Rose, J.C., 2006a. ‘Paleopathology of the commoners at Tell Amarna, Egypt, Akhenaten’s Capital City.’ Memórias Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Vol.101 (Suppl. 2), 73–6.

Rose, J.C., 2006b. ‘South Tombs Cemetery: the human remains’, in B. Kemp, ‘Tell el-Amarna, 2005–06.’ Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 92, 21–56.

Report on the human remains

Melissa Zabecki

Introduction

The third season of investigations at the Amarna South Tombs Cemetery was carried out during March and April of 2007. A swathe 35 meters by 5 meters was excavated by Wendy Dolling and crew. This swathe was adjacent to that excavated during the 2006 excavation season. Both of these areas represent a part of the cemetery that was not washed away down the nearby wadi over the centuries. This wadi was the subject of a systematic surface survey in 2005 that confirmed the existence of the cemetery in the first place. All of the skeletal material from these excavations was analyzed during the 2007 season by Melissa Zabecki and Professor Jerome C. Rose. Research questions that drove the analysis were formed, based on the past two years’ results. The peculiar demographical profile was a priority. Will this year’s excavation provide the same lack of infants as the past investigations? The pathological profile was also a consideration. Will there still be as much spinal trauma and anemia? Appropriate analyses were conducted to address these questions and the preliminary results are presented in this report.

Methods

When the skeletal material arrived at the lab each day, the provenience of the bones was recorded so that the material could be analyzed in the correct archaeological context. All of the material was dry-brushed with toothbrushes and paintbrushes. All cleaning was performed over a mesh screen to catch any cultural and biological material. Any materials such as skin, brains, and hair that fell off during cleaning was put in labeled bags and kept with the bones. Any cultural material such as linen or matting that fell off during cleaning was bagged with labels stating the provenience and set aside for specialists with the other cultural material from the cemetery.

After cleaning, basic data collection was conducted following the protocol specified by Buikstra and Ubelaker (1994). These data represent bone and tooth inventories, age and sex determinations, bone and tooth measurements, and pathological observations. Other specialized data collection included x-raying for different nutritional and biomechanical analyses, and gathering muscle marker information for workload studies over the coming year.

The skeletal material was separated into categorical groups for analysis and storage purposes. All of the material is in plastic crates and will be stored in the on-site magazine. “Individual” numbers refer to in situ burials that represent 50% or more of an individual found in situ. They have the full complement of paperwork and are crated separately. Some individuals share crates if space allows. “Cluster Individuals” are individuals who are represented by less than 50% of their bodies and were not in articulation, but were clearly a group of associated bones. They have analysis paperwork as appropriate and are crated with the miscellaneous bones by square and unit. “Skulls” are isolated skulls that could not be matched with any postcranial elements in the vicinity. They have skull paperwork, have all been photographed, and are stored in crates that only have skulls. “Mandibles” are isolated mandibles that had no associated skull. Each has mandible paperwork and was photographed. The isolated mandibles, like the cluster individuals, are crated in the miscellaneous bone crates by square and unit. The rest of the bones that were not associated with any particular individuals, clusters, skulls, or mandibles are inventoried in a general bone inventory file and are crated by square and unit with the cluster individuals and isolated mandibles.

Results and Discussion

The excavations of the South Tombs Cemetery resulted in the discovery of 18 individuals, 11 cluster individuals, 27 isolated skulls, and 8 isolated mandibles (Table 1). The condition of the skeletal material varied greatly, from very well preserved bone to salt-encrusted and sun-bleached bone that lacked any organic matrix. The maximum amount of information was gathered from each bone regardless of its condition, but some data, including simple age and sex determinations for certain individuals, were impossible to collect due to the poor preservation of some of the bone. This differential preservation complicates the integrity of any archeological skeletal sample.

Table 1. 2007 South Tombs Cemetery basic burial information.

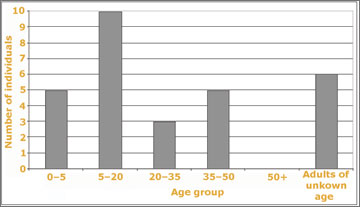

There is a major demographic concern with this particular skeletal sample, given by the fact that most of the individuals did not have skulls directly associated with their bodies. Counting both the isolated skulls and the individuals would result in an inflated demographic profile. We do know, however, that there were 27 isolated skulls, 20 individuals without skulls, and 9 individuals with skulls. Surely, 20 of the isolated skulls go with the 20 individuals missing skulls and the 7 other isolated skull probably either go with individuals in different squares, or individuals that were not identified due to the extensive robbing of graves and scattering of bones. So for the purpose of this analysis, we will use the demographic profile of only the individuals (with and without skulls) to discuss our findings. A total of 29 individuals were discovered during the 2007 excavation season. Of these 29 individuals, 3 were female, 6 were male, 2 were possible males, and 18 were individuals of undetermined sex. This distribution is similar to the last two years’ distribution, showing that there are more males and possible males (28%) than females and possible females (10%). This assemblage can also be considered by age groups (Figure 33). The age group distribution was similar to that of the past two years in that the largest age group represented was the children (5–20 years — 43% of the aged individuals). The low occurrence of infants (0–5 years — 22% of the aged individuals) continues to set the South Tombs Cemetery population apart from other populations where there are normally more infants buried than any other age group. Another similarity from past years is the lack of older adults (50+ years); though there was actually at least two older adults due to the presences of an isolated skull and isolated mandible (that do not belong to the same person). The number of young adults (20–35 years — 10% of the aged individuals) and middle adults (35–50 years — 17% of the aged individuals) was similar to past years.

Figure 33. Age groups represented in the 2007 South Tombs Cemetery excavations

The pathological profile of the 2007 material is similar to past years. Spinal trauma was seen in 4 individuals (Figure 34) and iron deficiency anemia was observed in 12 skulls (33% of all skulls) in the form of cribra orbitalia (Figure 35). (Note: as cribra orbitalia is only found on the skull, all 36 skulls are included in this count as opposed to only individuals figuring into the demographic analysis). These rates are similar to the 2005 and 2006 samples and corroborate the statements that Professor Rose made in previous reports about the people being subject to heavy workloads and having diets poor in iron. Other pathological observations included 6 individuals with slight osteoarthritis on one or more joint surface, 2 individuals with healed broken fingers, 2 individuals with healed broken ribs, and 2 individuals with healed broken clavicles. Two cases of spina bifida were also observed. This is a rare condition where the arches on the back of elements of the spine do not fuse and cause parts of the spinal chord to be exposed to possible injury (Figure 36). Most of the observed pathologies indicate that the population of the South Tombs Cemetery lived lives that included hard work and a low-quality diet.

Figure 34. Spinal trauma on Individual 27a. Note flaring margins of most vertebrae

Figure 35. Cribra orbitalia on Skull 57 (pointed out by arrows)

Figure 36. Arrows pointing to spina bifida on Individual 38